It all began in late July 2013, with fifteen of us gathered in a training room in South Melbourne on EWB’s Mickey Sampson Leadership Program. As part of the program, we were each invited to take on a personal project of our own choosing.

| Actually, that’s not true; it began much earlier than that at no particular point in time. You see, as an EWB volunteer I had often heard the phrase “humanitarian engineer” and wondered what it meant and to whom, exactly, it referred. Even those who used the term, I noticed, often couldn’t articulate what it meant beyond some vague, positive connotations. I felt sure it was worth asking for a proper definition, and to look for it using a medium that took others on that journey too. |  |

|||||

I felt sure it was worth asking for a proper definition, and to look for it using a medium that took others on that journey too.

There was never much doubt in my mind that a documentary would be that perfect medium. However, actually making one was just a musing fancy with no expectation of becoming real. I was an engineering/philosophy graduate with no experience in digital media, and I had plans for working, volunteering and following my usual pastimes without some ridiculous step into an unknown discipline, thank you very much! – that is, until the Mickey Sampson program and a few months of pre-employment free time came along.

So those were the driving questions: What and who is a humanitarian engineer? Can all engineers be humanitarians, and if so, in what sense can we consider them so? My next question was: How the heck do you make a documentary?

My next question was: How the heck do you make a documentary?

I found some answers from the online film-making community, whose altruism and generosity is an ongoing source of gratitude and bafflement to me (some of my early friends). The first two weeks were spent just finding my feet, trying to familiarise myself with what the doco-making process would involve. I ran with the advice I found – humbled to have this great trove at my fingertips – but by the end, I could answer it for myself, if not “correctly”, at least personally. Here is my answer.

Early Promotion

Planning

Research

Storyboarding

Crowdfunding

Buying equipment

Maree

Interviewing

Shooting B-roll

Sourcing B-roll

Narration & voiceovers

Post-production

Editing

Promotion

The… end?

Early Promotion

I was taking on the project alone, so I created a Facebook project page to build a support base. It gave me moral vindication and a psychological boost to know that others believed in the initiative. And it was also an investment in later promotion, as I figured that people would be more interested to see a documentary they’d been following from the start!

The Facebook page would also act as a pool for me to draw volunteers. I thought of it as a rent-a-crowd resource: carving out my own advertising space, I guess. From it, I built up a database of people who had offered encouragement, support and general help and those who could also contribute in specific ways. To my astonishment, these turned out to be friends and strangers alike.

The project page also kept me in check, as I felt (realistically or not!) that I had someone and somewhere to report to, and that people cared!

Planning

It’s a personal trait: I am anal about planning, documentation and project management. My lifeline from the beginning of this project has been an Excel spreadsheet that has since swelled to 30+ worksheets. Initially it contained just four: Schedule, Budget, Resources and Interview Wishlist. I soon created a live sheet called To Do Lists which gave me a look-ahead of the tasks for the coming weeks. I was quickly, very quickly, learning that solo documentary-making was extremely multidisciplinary and also required a lot of multi-tasking, so the planning documents were crucial to stay on top of things!

I was quickly, very quickly, learning that solo documentary-making was extremely multidisciplinary…

Research

How have other people answered the question, What is a humanitarian engineer? How does the humanitarian sector define it? What about the dictionary? Is there an authority, and what are the competing theories?

As well as answering these questions, I needed to identify relevant people to consult and create the content of my documentary, which meant snooping out organisations, individuals and relevant events. The mighty Resources worksheet continued to blossom, as did the Interview Wishlist!

I suppose it comes under Research that this was a time of contacting many people in the humanitarian engineering space – in Australia by design, but sometimes internationally. From cold-calling organisations hoping to find suitable interviewees, to targeting individuals and pursuing any means to reach them, this was an exciting time. I had a quota of sectors I wanted to cover and a breakdown of the number of talking heads allocated to each. I made countless phone calls and emails and every response in my inbox was met with a flutter of anticipation. My moods peaked and troughed in sympathy with the enthusiastic agreements, apologetic declinations, geographical barriers encountered, frustrating evasions and countless referrals I received.

…this was an exciting time. I had a quota of sectors I wanted to cover and a breakdown of the number of talking heads allocated to each… Every response in my inbox was met with a flutter of anticipation…

I also had to research several historical subjects. Aside from the semantics of “humanitarian”, there was a lot of background knowledge to take in about the history of the humanitarian sector, the relationships between the military/NGOs/government around aid delivery (which didn’t make the final cut), and the appropriate technology movement of the 1970s. Even now, I’m certain there’s many a stone I left unturned.

Storyboarding

It’s tricky to place this one chronologically, because in many ways it was the first thing and the last thing that I did. In short, it was iterative. Loosely at the same time as my research, it evolved through a mess of sketchy plans that were thick with arrows, illegible asides and sticky tape.

…it evolved through a mess of sketchy plans that were thick with arrows, illegible asides and sticky tape.

The structure of the documentary emerged quite early and, surprisingly, didn’t alter dramatically throughout the filming and editing stages. At this point, I “wrote” the story through narration – as much as I could, of course, because the rest of the story needed to be “written” after the interviews; they would shape the content, naturally, of the final product, and more importantly they would be the vehicle to reveal the story, not just tell it.

So after the interviews, my tatty, scrawled storyboard took on more detail, progressing to a level of complexity unwise to tackle without the help of electronic word processing. My laptop was promoted from a mere research machine to a canvas. I don’t know what the pros call it, but my so-called Dissected Storyboard was a mother of an Excel worksheet that specified every planned cut, every still image, every piece of narration and so on that I envisaged to be used in the documentary, and where. This would be the recipe for the documentary, its electronic DNA.

I don’t know what the pros call it, but my so-called Dissected Storyboard was a mother of an Excel worksheet that specified every planned cut, every still image, every piece of narration and so on that I envisaged…

However, this stage was a long way off… Let’s get back to those early research/planning days when the storyboard was scrunchable and tearable.

Crowdfunding

Vision and energy are inherited; money, you have to find yourself! By incident, I’d attended a crowdfunding information session the previous month, which I left bubbling with excitement and convinced that StartSomeGood.com would be the ideal platform to crowdfund my project. One of their founders, Tom Dawkins, was very encouraging and I found the whole SSG team amazing to work with from the get-go. My target was $1700 within the 30-day campaign; I raised $1885, which was a welcome surprise.

Buying equipment (and figuring out how to use it)

Again, more research was involved here – including making a nuisance of myself to any friends and family who had remote knowledge about cameras (even better, DSLRs, and even better, if they shot moving pictures with it.) My overseas cousin, a passionate maker of short films, was invaluable; his legendary essay-length emails were a trove of the advice for which I was so hungry in my self-conscious ignorance.

I might’ve been ignorant about the filmography world, but I put my miserly nature to good use by securing good deals on a secondhand Canon 600D DSLR+kit lens, high-speed SD cards to handle the HD writing, two-point lighting set-up, reflector, shotgun mic and lapel mic from eBay and Gumtree.

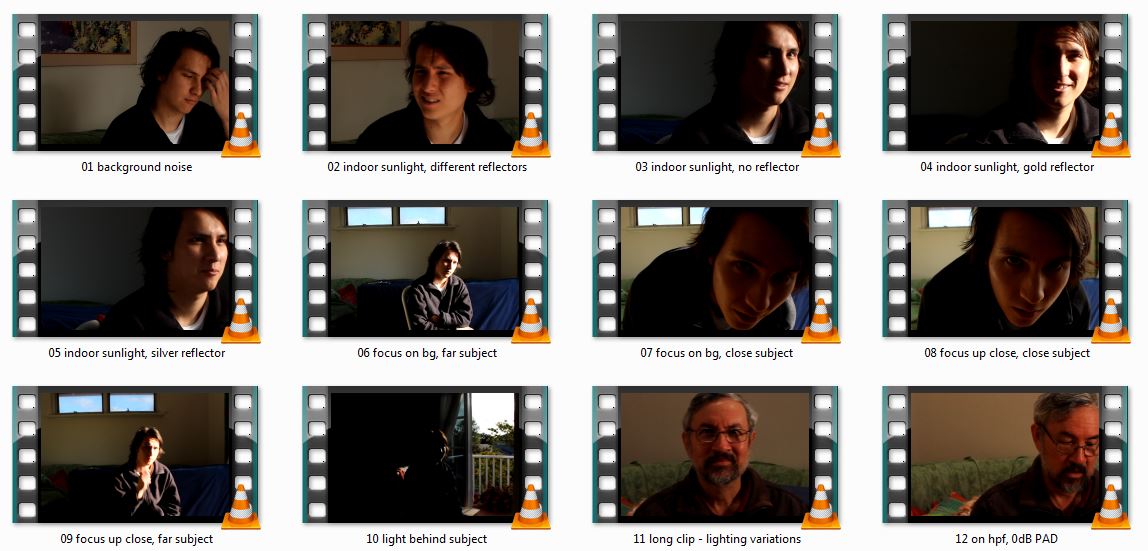

And then there was the matter of figuring out how to use it all. It didn’t come all at once, so I had time to befriend my new devices with doting care and curiosity. My friends, sister and dad were extremely patient with me as I plonked them down in various places and fiddled with settings, eliciting speech, smiles and shifts on demand and so on; I so appreciate their forebearance.

All this practice was the bare minimum to be able to use the equipment. I would never for a second consider myself good at filming or photography, let alone being anywhere near a buff. I was starting, honestly, from ground zero, and by the end of it had worked my way up to perhaps a lowly 2 or 3… on a scale that stretches to 100. But ultimately, you can only learn through practice, and you do pick up the tricks you need along the way.

All this practice was the bare minimum to be able to use the equipment.

Because I was hyper-aware of my novice status, I tried to be diligent about my learning and kept a diary with all the experimenting sessions noted and reflected upon. It does sound terribly academic, and I certainly felt that even as I was doing it, but I didn’t really know any other way to go about it.

It does sound terribly academic, and I certainly felt that even as I was doing it, but I didn’t really know any other way to go about it.

Sometimes I think it would’ve been really nice to have a mentor with me all the time (in real life) to show me things first-hand, because most of my advice-receiving avenues were of the telling and trouble-shooting sort. But I’m grateful all the same.

Maree

Speaking of mentors, I should mention the wonderful Maree Zannis, a friend and fellow participant on the Mickey Sampson program. She and I made a pledge to keep each other updated on our projects (preferably weekly, although this worked better in theory than practice) and support each other across the breadth of the Australian continent: she from Melbourne, I from Perth.

Having Maree’s support was awesome; not only is this girl seriously the most encouraging, lovely person you can find, but just being able to brain-dump onto a listening ear can be hugely beneficial when 70 things seem to be going on at once, when you’re fretting about matter x while keeping an eye on matter y while feeling woefully incompetent on both of them and more, and when the plethora of these tasks flatten out and lose their distinction and sense of priority. Maree’s “Pinky Promise Updates” allowed me to refocus and take stock on a regular basis, even more so than the live To Do Lists worksheets. Thank you, Maree!

(Maree is starting up a humanitarian engineering magazine so watch that space!)

Interviewing

The actual interviews each took 1-2 hours, sandwiched by much longer hours of work on each side. After the individuals were contacted and arrangements made (often through HR staff), I did further background research on them and their organisations, wrote and pre-sent question lists, and advertised for helpers to act as my filming buddies. The Facebook page was handy for recruiting volunteers, as was the network of EWB members scattered throughout Australia. My interviewees resided in Perth, Melbourne, Sydney and Canberra, so creating an efficient but accommodating interview schedule was a logistical challenge. With their cooperation, things worked out well and I only had to film one interview remotely.

I stayed at friends’ houses when I was in Melbourne and Sydney; Glen and Luan have my thanks for their hospitality over this intensive few days of interview/upload/recharge x8.

|

|

|

After each interview, transcripts were generated and every piece of footage had to be indexed with key topics, quotes, time markings and so on. This could take up to several days of work; there was a lot of content to digest from our conversations, let alone record, as they were also quizzed on many topics that didn’t make the final cut in the documentary.

|

|

Hindsight is a greater honer of sensitivity. There is a certain art to interviewing for film to which I was blind at the beginning, in spite of all my wide-eyed diligence. Skill in that art pivots on one principle: being constantly mindful of how you’re going to cut the scene. For example, if the interviewee says, “As I said,” they’ve effectively forced you to include the bit they said before. And if their sentences run on and they leave their conjunctions dangling, they lock you into including their whole spiel or else making some very abrupt cuts.

Interviewees are also, oftentimes, self-conscious at the beginning, so it’s worthwhile to end the interview with the questions you asked first up. And it’s invariably wise to keep your own mouth shut; nothing beckons discourse like silence, and nothing maddens so much when you’re editing as a beautiful quote ruined by your own “mmm”-ing or interjections.

…it’s invariably wise to keep your own mouth shut; nothing beckons discourse like silence, and nothing maddens you so much when you’re editing as a beautiful quote ruined by your own “mmm”-ing or interjections.

I also encountered a whole raft of environmental factors that, erstwhile unconsidered, soon made their presence known (office doors closing, trains passing, tools dropping, etc.) And then there are the technical considerations of using any equipment, such as getting a feel for how your camera responds to lighting changes. My notebook soon became a repository of lessons learnt – or killer regrets, depending on your outlook.

My notebook soon became a repository of lessons learnt…

Taking off my producing hat for a moment, the interviews themselves were fascinating. It was an honour to meet people with such different experiences and outlooks, and I found them invariably warm and intelligent. I’m glad that being privvy to their monologues was some incidental reward for my filming helpers, who were managing second cameras and keeping an eye on equipment while I did all the questioning and nodding.

I was definitely learning on the job, and it must be admitted that I had to re-shoot two interviews to my satisfaction. Luck or providence played a big part in at least one of them; she fitted in a re-shoot just hours before catching a plane, and I felt like heaven was smiling on me!

Shooting B-roll

After filming, transcribing and indexing the interviews, I revisited my storyboard and took it to the next level of existence: from physical to electronic (see Storyboarding). But my Dissected Storyboard was telling me to invoke a whole bunch of shots that I didn’t have, which needed to be either shot by me or sourced externally. I did both.

The term B-roll, for those unacquainted, refers to the footage that accompanies the primary content of the scene (which may be voiceovers, interviews or the main narrative thread), serving to illustrate or complement the ideas presented there. Shooting B-roll footage meant taking my camera to various locations according to the shots I had prescribed for myself. Again, I was following a very prescriptive approach to making the documentary, always planning before doing, hence the centrality of those Excel worksheets I keep harping on about. This seems, to me, a natural way to operate, but I would be really interested to compare my modus operandi to a professional’s (or a more experienced non-professional’s) workflow.

Again, I was following a very prescriptive approach to making the documentary…

As with the interviews, every clip was indexed to maintain a comprehensive record of all the shots I’d taken including descriptions, time-marks, remarks, category of use, etc. – a time-consuming process.

Sourcing B-roll

I think of the footage I didn’t shoot in terms of two main categories, although the lines often blur: externally-sourced footage (from the internet, either with Creative Commons licences or copyright-held and requiring personal permission to use) and contributed footage (from the individuals I interviewed or their organisations). This includes video footage, stills and audio files.

Using other people’s footage opened up a whole new world of research for me, as I had to get cluey about different types of licences and copyright laws in Australia and overseas. My bedtime reading for a time consisted of the Australian Copyright Council’s handbook on permissions and clearances, which is actually not as dry as it sounds. This was all another huge learning curve, taking me plenty of time to hack through legal jargon let alone source the footage that I required!

My bedtime reading for a time consisted of the Australian Copyright Council’s handbook on permissions and clearances, which is actually not as dry as it sounds.

Most of the footage I was seeking was quite specific (e.g. the Schumacher lectures, the case study of failed appropriate technology, etc.) as I’d tried to shoot as much generic footage as possible myself.

Sourcing B-roll footage was largely a return to the Research phase: looking up appropriate material, contacting relevant people, learning about the legal frameworks and so on. There are a lot of databases out there, and while it’s a privilege to be able to trawl through them all, it’s certainly time-consuming to differentiate and get a feel for what to look for where – and how much to expect to pay!

Contacting copyright-holders was another task that took a lot of time, which was pursued through emails, phone calls, people-who-know-people and leaving messages on blogs, websites and Wikimedia user boards. The Excel worksheets were very handy for keeping track of all these communication attempts.

Speaking of research, the interviews had breathed new life into the storyboard, so that itself required a return to the concepts in the documentary and topping up my knowledge in several areas. Who says research skills are just for academics?

Narration & voiceovers

These were recorded simultaneously to the B-roll footage and several friends jumped on board to help me as I reluctantly changed sides of the camera. Kung Kung (Grandpa) being unwell, my family took a 3-week trip to Kuching and Singapore, and when not visiting hospital or sitting on Kung Kung’s bed at home, I was conscious to not lose momentum on the filming. My younger cousin – by incident, I learned, an aspiring film-maker – was on school holidays and happily became my sidekick, helping me shoot both narration and B-roll sequences.

The voiceovers were recorded multiple times back in Perth. As usual, every clip had to be indexed and labelled with a reference code. I must admit it took some deliberate effort to stop my self-imposed protocols (honestly, I am such a bureaucrat! It’s terrible!) from standing in the way of my willingness to re-record footage when necessary. The following mantra became helpful: Procedures must serve the recording process, not the other way round! As much as I disliked the nuisance, I admitted I needed to re-record all my voiceovers very late in the editing stage; hands down, it’s worth it if the quality of the documentary improves by even a smidgen.

I admitted I needed to re-record all my voiceovers very late in the editing stage; hands down, it’s worth it if the quality of the documentary improves…

There was, I admit, some dubbing involved for particular on-screen narrative segments where noisy birds and traffic made voice audibility a write-off. After re-recording myself by lip-syncing (I do not recommend this to anyone), it was a matter of reconstructing the background environment by adding controlled levels of ambient sounds on separate tracks. The whole dubbing experience was a delicate, fiddlesome and ultimately controversial one, but it’s the price I paid for salvaging the nice visuals shot by my friend with a fancy camera. I didn’t have the heart to re-record those narration scenes – perhaps to my downfall. It’s a lingering point of anguish for me.

Post-production

In nearly all productions, there’s some wizardry that goes on between what’s captured by the camera and what the viewer eventually sees (and hears). I can’t overstate how much I felt like an imposter doing all the post-production techniques myself. Honestly, it is a real craft to do a cracker job of cleaning up audio files, bringing them to ace quality, colour-correcting images and, further to that, colour-grading them to yield the best picture. The professionals and serious amateurs out there have finely honed their abilities. It requires excellent perception, wise judgment and immense skill of execution – and a lot of experience to develop these! I found myself lacking in all, but again, the advice online and from friends and family was a lifeline. And there’s really no substitute for practice.

I can’t overstate how much I felt like an imposter doing all the post-production techniques myself.

A lot of time was spent simply watching and soaking up the information on forums, Youtube, Vimeo, mentor messages and whatnot (I have a whole stack of Bitly bundles with the most helpful tutorials filed away for reference.) It was important to learn as much as I could about post-production techniques not just after all the filming was done, but during and before, so that I knew, at least, the basics of what was possible (or realistic) to achieve in post-production – and what I’d have to guarantee during the filming as no amount of EQ or colour-masking could save!

Audio post-production became the bane of my documentary-making existence. Right till the end, I was battling unbalanced voiceovers and the effects of having recorded in poor sound environments… as well as the legacies of my early (typically green) heavy-handedness with noise-cancelling and EQs. I still don’t think I got it right by the end, and without doubt I’d cite audio handling as one of my most serious flaws on the project. I take my hat off to those who have mastered it.

I still don’t think I got it right by the end, and without doubt I’d cite audio handling as one of my most serious flaws on the project.

Editing

I absolutely adored this part of the project. It was not only the time when everything began to “feel real” and take form (perhaps like giving birth after months of labour and conception? – or so I imagine). But more than that, it was the phase in which creativity could be unshackled a little more and details doted upon without guilt of nit-picking – and I love nothing if not exercising a little artistic liberty and losing myself in details. So while I was a complete newcomer to the business, editing saw me somewhat more in my element.

…it was the phase in which creativity could be unshackled a little more and details doted upon without guilt of nit-picking…

…literally. I had originally purchased an Adobe software called Premier Elements upon reading good reviews, but opening the program, my heart dropped like a stone; it had nowhere near the sleekness and complexity of Adobe Premier Pro which my friend had briefly run me through several weeks before. This is no criticism of Elements, and I’m sure it would’ve sufficed, but on the matter of editing I was hungry for the very best and clouded by desire: I wanted Pro! The stars aligned when I found an even better deal on the superior software and the kind folk at Adobe let me swap my investment.

I was elated and took to my new toy with devotion, making short practice videos to promote my aunty’s cafe (Tolido’s) and International Day for People With A Disability. This all happened around Christmas 2013 when I was in Kuching visiting relatives. Unforgivably, I was late for our Christmas Eve dinner, detained by the magic of video editing.

Unforgivably, I was late for our Christmas Eve dinner, detained by the magic of video editing.

Although I said that editing was quite a creative process, I actually approached it (at least, the rough cut) in a fairly formulaic way. My Dissected Storyboard and intricately indexed clips contained enough detail to prescribe the way the documentary would be sewn together. Of course, I departed from this several times, but a good amount stayed true.

I want to emphasise that editing occured at the same time as a lot of the tasks above: sourcing footage, audio and video post-production, and so on. The linear workflow one imagines has more conceptual than practical merit, with no respect for the gnarliness of the real world!

Promotion

In many ways, the promotion of the documentary has been ongoing: from the outset it was orchestrated to sit in other people’s minds through the Facebook page, through the crowdfunding campaign and through shamelessly name-dropping the concept to as many people as I encountered who might even be remotely interested (and not, for that matter).

But as launch date is nigh, the promotional efforts naturally step up and the goals I pursue to this end are to create a website, make and distribute a trailer, organise public screenings in collaboration with Engineers Australia and draw on as many networks as possible to get the documentary into the public arena.

I hope that groups with an interest in this documentary will hold their own screenings, and to this end I invite them to contact me and utilise the suggested resources to run such an event.

The… end?

I’m not sure there’s an end in sight; I hope it will be watched attentively by people in a long time to come: engineers and non-engineers and self-proclaimed humanitarian engineers alike. If the idea of engineers as humanitarians enters the consciousness of at least one specimen of each of these, I will deem it a success.

In fact, I will deem it a success even if it is, ultimately, nothing more than a proof-of-concept for a better humanitarian engineering documentary to be made in the future, by someone with more skill who will say more, say it better, and reach further. I would love that.

I will deem it a success even if it is, ultimately, nothing more than a proof-of-concept for a better humanitarian engineering documentary to be made in the future…

In any case, the huge journey of learning – technical, conceptual, social, individual and more – has made the creation of this documentary, to me, a worthwhile experience in itself. I’m 98% sure I’ll put down the camera for a while. That said, I confess that one of those 30+ Excel worksheets is a topic map of The Humanitarian Engineer with a rather extended footnote for at least seven sequels that ought to follow…

Any takers?